This interesting piece from New York Magazine (ironically, a magazine not really known for its writing) seeks to ask posthumously, What was the Hipster? While I wouldn’t say that this hipster phenomenon is totally dead, it certainly has peaked and been fully commercialized. The line between where hipsters end and everyone else begins has just seemed to end. This author claims hipsters started in the late nineties and evolved over the last decade. While I think a lot of this article is incessant babbling and uses one too many “big words” to show off, there are some clever observations. He essentially chronicles what led to the end of hipsterism as being an alternative trend and more of an adopted, commercialized mainstream trend. It became something cool and new, that you could buy at Urban Outfitters. Essentially you could be an individual, just like everyone else:

“The rebel consumer is the person who, adopting the rhetoric but not the politics of the counterculture, convinces himself that buying the right mass products individualizes him as transgressive. Purchasing the products of authority is thus reimagined as a defiance of authority. Usually this requires a fantasized censor who doesn’t want you to have cologne, or booze, or cars. But the censor doesn’t exist, of course, and hipster culture is not a counterculture. On the contrary, the neighborhood organization of hipsters—their tight-knit colonies of similar-looking, slouching people—represents not hostility to authority (as among punks or hippies) but a superior community of status where the game of knowing-in-advance can be played with maximum refinement. The hipster is a savant at picking up the tiny changes of rapidly cycling consumer distinction.”

He also sums up well why their is so much anger and resentment around hipsters and hipster trends:

“This in-group competition, more than anything else, is why the term hipster is primarily a pejorative—an insult that belongs to the family of poseur, faker, phony, scenester, and hanger-on. The challenge does not clarify whether the challenger rejects values in common with the hipster—of style, savoir vivre, cool, etc. It just asserts that its target adopts them with the wrong motives. He does not earn them.”

And finally he makes an interesting point that at its core there is small number of people actually writing, creating art, and contributing to items they’ve made to the public. And most of the other people around them are just consuming the trend:

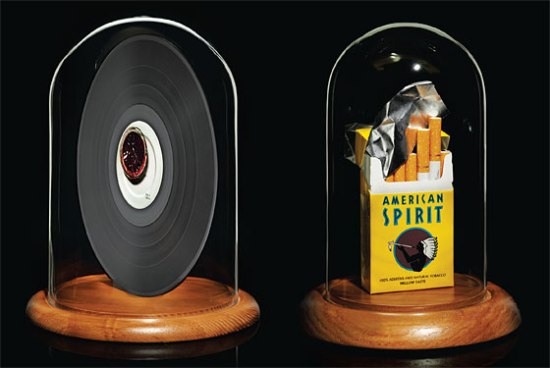

“It has long been noticed that the majority of people who frequent any traditional bohemia are hangers-on. Somewhere, at the center, will be a very small number of hardworking writers, artists, or politicos, from whom the hangers-on draw their feelings of authenticity. Hipsterdom at its darkest, however, is something like bohemia without the revolutionary core. Among hipsters, the skills of hanging-on—trend-spotting, cool-hunting, plus handicraft skills—become the heroic practice. The most active participants sell something—customized brand-name jeans, airbrushed skateboards, the most special whiskey, the most retro sunglasses—and the more passive just buy it.”

Hipsterism was a trend centered around being alternative, unique and against the mainstream. And somewhere along the line small pieces of these trends seeped there way into popular culture and next thing we knew we all had to have them (think flannel, indigenous print shirts, skinny jeans, Rayban sunglasses, and summer scarves. We hate that the only thing that is hip in the moment is everything hipster, and that somehow we can’t escape it.

Read the whole article by Mark Greif here.